Why Biotech Executives and Investors Should Understand the Hidden Cost of Methodological Rigidity

If you’ve spent any time in the biotech space—as an executive navigating a financing round, an investor underwriting a deal, a board member reviewing portfolio valuations, or a CEO setting strike prices on employee options that actually help recruit a world-class team—you’ve probably experienced a familiar friction. Your valuation team or auditor applies a methodology that feels technically sound on paper but somehow fails to capture the actual value dynamics of the matter at hand. The common stock valuation that determines your 409A strike price, the portfolio mark that shapes your investor narrative, the enterprise value that anchors your next financing—the numbers are quantitatively defensible but are just not quite right and don’t sit well.

The trap is this: in biotech, the most auditable valuation is often not the most decision-useful valuation.

This isn’t anyone’s fault. Your auditors are doing their job and doing it diligently. But there’s a structural issue at play that biotech stakeholders should understand: the very frameworks designed to bring consistency and rigor to valuation, when applied too rigidly, impose a significant cost—one that affects how assets are priced, how capital is allocated, and ultimately how innovation is funded.

Order, Disorder, and the Edge of Innovation

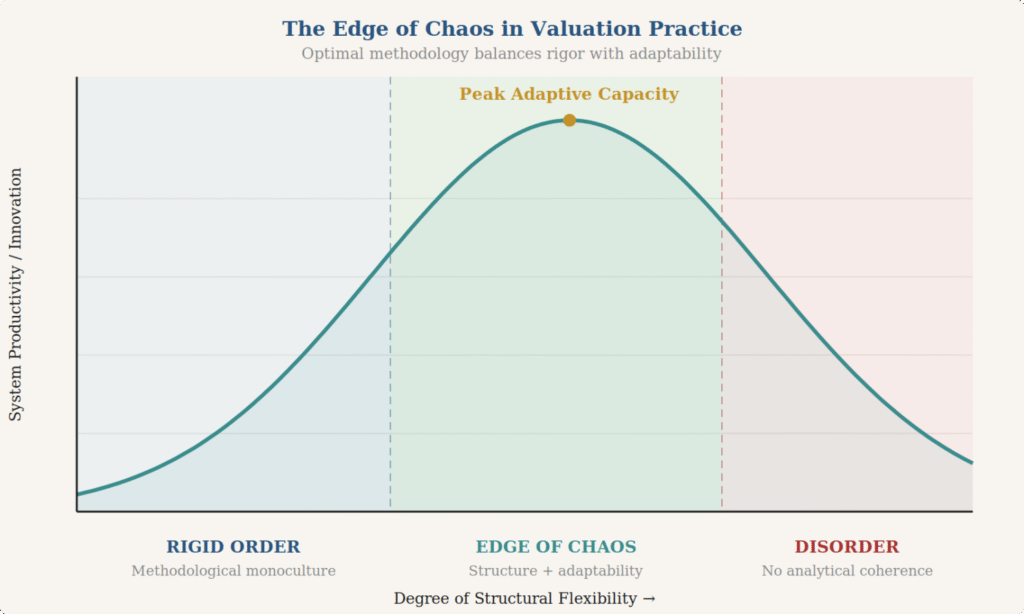

In complexity science, healthy systems are those that can navigate between order and disorder. Too much order or too much rigidity and a system loses its ability to adapt, innovate, and respond to changing conditions. Too much disorder, and the system descends into chaos. The most productive zone is the one in between: the “edge of chaos,” where enough structure exists to maintain coherence, but enough flexibility remains to allow for experimentation and improvement.

Capital markets operate by the same principle. In market terms, we describe order as efficiency and disorder as volatility or dislocation. The insight that many people miss is that disorder is not inherently bad. Volatility is the price of returns. Market dislocations are the mechanism through which capital gets reallocated from less productive to more productive uses. Creative destruction, Schumpeter’s famous concept, is precisely the productive use of disorder to drive progress.

Biotechnology, of all industries, should understand this intuitively. The entire venture-backed biotech model is a structured bet on productive disorder: high failure rates, massive uncertainty, and nonlinear outcomes are not bugs in the system, they are features. The disorder of clinical trial failures, strategic pivots, and competitive disruption is what allows the ecosystem to explore the solution space and occasionally find breakthrough therapies.

Where Practice Aids Become Practice Limits

Now consider what happens when we introduce structure like valuation standards and practice aids into this environment. Pronouncements like ASC 820, the AICPA’s valuation practice aids, and the International Private Equity and Venture Capital Valuation Guidelines were designed with laudable goals: to create consistency, comparability, and defensibility in how assets are valued. At a basic level, they succeeded. They established a common language, reduced outlier practices, and gave auditors a workable framework for evaluating reasonableness.

But there’s an important distinction between a framework that enables good practice and a framework that defines good practice. When that line blurs, as it tends to do in audit and compliance environments, the practice aid becomes the ceiling rather than the floor. The map becomes the territory.

This is not a criticism of auditors. Auditors are trained, and rightly so, to prioritize consistency, defensibility, and compliance. They are convergent thinkers in a role that demands convergent thinking. When you hand a practice aid to a population selected for these traits, they will naturally treat it as the authoritative source on methodology, not as a starting framework to be adapted based on context. They’re doing exactly what they’re trained and incentivized to do.

It is worth noting that the AICPA Practice Aid is explicitly nonauthoritative guidance. The AICPA itself states that its accounting and valuation guides are “a source of nonauthoritative accounting guidance.” The Practice Aid establishes best practices, not binding standards, and there is meaningful room within the professional framework for practitioners to adapt methodologies to the assets they are valuing. Yet in the audit ecosystem, this distinction can largely collapse. The nonauthoritative guide often functionally becomes the envelope of permissible methodology—constraining not just how high or how low a valuation lands, but which analytical approaches are considered acceptable at all.

The problem arises when this natural conservatism is applied to assets whose value dynamics don’t fit neatly into the standard toolkit. And biotech assets are, almost by definition, those assets.

The Cost You May Not See

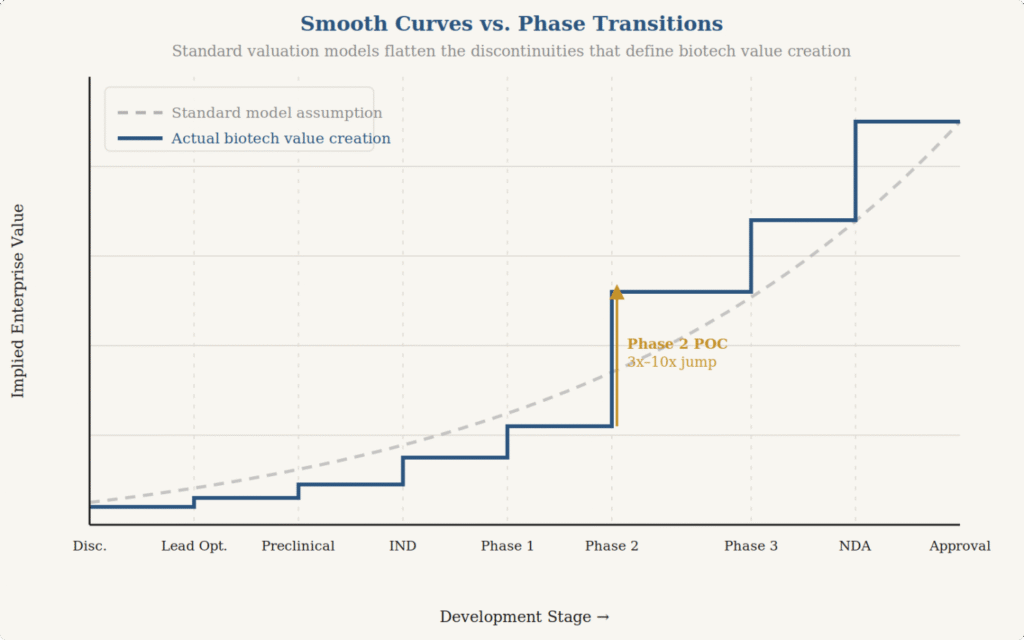

Consider the standard approaches most commonly applied to early-stage biopharmaceutical assets: discounted cash flow models with risk-adjusted net present values, probability-weighted expected return models, and market comparable analyses. These are all legitimate tools. But they share a common limitation when applied to biotech: they tend to smooth over the very discontinuities that define how value actually moves in this space.

Biotech value creation is not linear. It is characterized by phase transitions—moments where a single data point, a regulatory decision, or a competitive development can cause a step-change in the entire value profile of an asset. A Phase II readout doesn’t incrementally increase value along a smooth curve; it either validates or invalidates a thesis, often creating a 3x to 10x change in implied value overnight. Risk-neutral probability frameworks, while elegant and auditable, flatten these transitions into smooth expected value curves, which is precisely the wrong model for assets whose value evolution is fundamentally discontinuous.

Put simply: biotech value doesn’t rise like a ramp. It moves like stairs—long flat stretches punctuated by sharp jumps up or down at each clinical milestone. Standard frameworks draw the ramp. The stairs are what’s real.

Consider a real-world consequence. A pre-IND biotech closes a Series A at $80 million pre-money. The standard OPM backsolve produces a 409A valuation that sets the common stock strike price at roughly 35% of the preferred price—technically defensible, fully auditable. But it’s high enough that the VP of Biology the company needs to recruit can get a comparable equity package at a Series B company carrying less science risk and a clearer path to value inflection. The methodology produced a number. The number cost you the hire. The hire was the single most important driver of whether the science succeeds. That’s the cost you may not see on the valuation report, but you’ll feel it in the lab.

Meanwhile, approaches that are arguably better suited to the actual structure of biotech value creation—real options methodologies, scenario-based frameworks that account for path dependence, Bayesian approaches, adaptive models that incorporate competitive landscape dynamics—remain underutilized in practice. Not because anyone has evaluated them and found them wanting, but because they sit outside the comfort zone of the practice aid ecosystem. Auditors are understandably cautious about methodologies that lack a clear lineage in the guidance literature, and so the methodological frontier stagnates.

This is the hidden cost of artificial rigidity: a methodological monoculture that is degrading valuation quality for the asset classes where getting it right matters most.

What Executives and Investors Should Know

None of this means you should be adversarial with your audit team. They are professionals doing important work, and the standards they enforce serve a vital function in maintaining market integrity. But as a biotech executive or investor, you should be aware of a few things.

First, understand that the methodology applied to your assets is not necessarily the most accurate methodology—it may simply be the most quantifiably defensible one. These are different things, and the gap between them can be significant in biotech. Defensibility is about surviving an audit review. Accuracy is about capturing how value actually moves in your pipeline. Both matter, but if you only optimize for the first, you may be making strategic decisions based on an incomplete picture.

Second, recognize that you have a role in this conversation. Valuation is not something that happens to you—it’s a process you participate in. If your valuation provider is defaulting to a standard methodology without engaging deeply on the specific dynamics of your asset, your pipeline, or your competitive position, that’s a conversation worth having. Ask why a particular approach was chosen. Ask what alternatives were considered and why they were set aside. The goal is not to challenge the auditor’s authority but to ensure that the analytical rigor matches the complexity of the asset.

Third, be cautious about the downstream effects. When valuations are systematically produced using frameworks that under- or over-weight optionality, ignore path dependence, or smooth over phase transitions (product as well as capital and market based), the impact ripples outward. It affects fundraising narratives, portfolio marks, strategic decision-making, and ultimately the allocation of capital across the innovation ecosystem. If the analytical tools we use to value biotech don’t reflect how biotech actually creates value, we risk systematically mispricing the future.

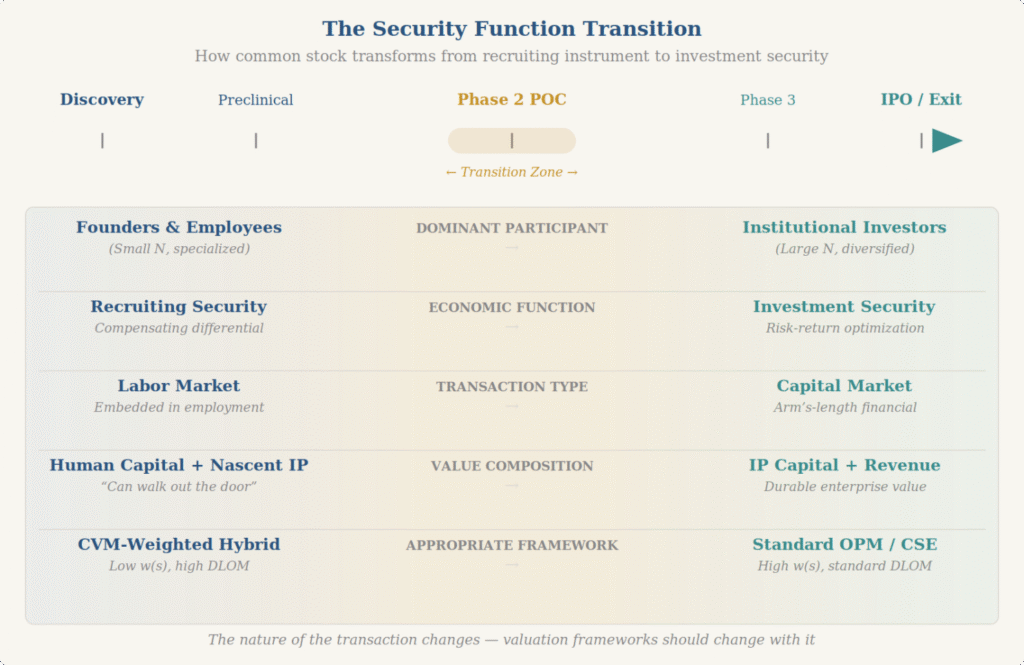

Fourth, recognize that the universe of relevant stakeholders shifts as a company matures—and valuation frameworks need to shift with it. In the early stages of biotech formation, the two most important valuation decisions are getting venture capital in the door and recruiting top talent. The purpose of venture capital in biotech is to progressively transform financial capital and human capital into technology and IP capital. As this transformation unfolds, the universe of market participants—the willing buyers and sellers whose perspectives define fair value—changes fundamentally. Markets with a handful of specialized participants behave very differently from markets with thousands of anonymous traders, and the valuation frameworks appropriate to each are correspondingly different. An informed valuation perspective must understand the transformation of “common as a recruiting security” into “common as an investing security,” and it must identify the transition points at which that shift occurs. Getting this wrong—in either direction—misprices the security for the actual participants in the market.

Finding the Edge

The healthiest systems, biological, economic, or otherwise, are those that can operate at the edge between order and disorder. In valuation practice, this means maintaining the consistency and rigor that standards provide while preserving the intellectual flexibility to adapt methodologies to the assets they’re meant to describe. It means treating practice aids as foundations, not fences. It means allowing the productive “disorder” of methodological innovation to coexist with the “order” of audit defensibility. What it really means is that the valuation provider—and the auditor—needs to fundamentally understand the industry dynamics for the companies, assets, and securities they are evaluating. They need to understand when models work and when they break down, not just what everyone else is doing or what is most easily auditable.

The Practice Aids for common stock valuation and portfolio valuation were largely shaped around patterns more common in software and technology investing than in milestone-driven biotech. Financing overhang, negotiating leverage, differentiated risk utility functions among market participant groups, therapeutic modality trends, regulatory dynamics, investor psychology—these are all distinctive features of biotechnology investing that need to be captured in valuations that actually make sense. If you can’t recruit the right team because someone’s mathematical solution automatically imputes value creation when it has not yet been created, is that really helpful? There is a difference between value now and not yet. Intelligent valuations bridge that gap in a reasonable manner.

Your audit team is doing their job. The question for biotech executives and investors is whether the tools they’re using are helping you do yours.

About RNA Advisors

RNA Advisors helps biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies translate scientific and clinical value into investor-ready narratives. Our valuation frameworks are built specifically for milestone-driven biotech—modeling phase transitions/value inflection points explicitly, aligning methodology to the actual market participants at each stage of development, and preserving the optionality that standard approaches tend to flatten. Through rigorous financial modeling, market research, and analytical frameworks built for the unique dynamics of life science assets, we bridge the gap between breakthrough science and effective capital formation.